There’s been a belief in professional tennis over the past 40-50 years that grass is yesterday’s surface. Out of respect for Wimbledon’s heritage, grass is tolerated for 4-5 weeks a year with a handful of tournaments, but basically tennis these days is played on hard or clay courts.

It’s been a slow but ruthless evolution. In the early 1970s, as the top-level tennis circuits grew accustomed to being able to welcome amateurs and professionals (up to 1968 no-one could play the traditional tournaments if they were paid money, at least above the table), most of the leading tournaments were on grass, with a good smattering on clay. But then things changed.

The grass that had hosted the US Open at Forest Hills was so poor it was always a bit of a lottery, and in 1974 it was abandoned, first for clay and then for hard. In 1987, the Australian Open abandoned grass for hard, and even Wimbledon’s grass wasn’t great – watch the great Borg-McEnroe tiebreak from 1980 and you’ll see numerous bad bounces. Players rushed to the net to reduce the potential for unpredictable bounces as much as for the satisfaction of hitting a crisp volley.

But in the last 30 years there has been considerable investment in sports turf technology, to the point where grass courts are very different today. Yes, there are still bad bounces, but relatively few, and there are on clay too. And something remarkable has been happening, especially in the past six weeks of the global grasscourt season – a number of players have said the grass season should be longer.

So can the damage wrought by 50 years of retrenchment from grass be undone? Not all of it.

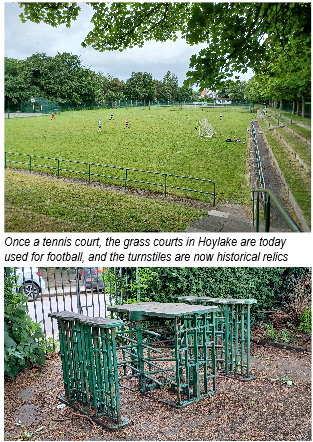

In the early 1970s, there was a healthy grasscourt season for the four weeks after Wimbledon which attracted the world’s top players of the time. British venues like Felixtowe, Frinton-on-Sea, Hoylake and Ilkley hosted tournaments, and there were events on the North American grass in the run-up to the US Open at Forest Hills.

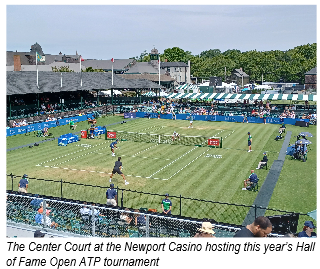

Apart from Newport in Rhode Island, which has the slot the week after Wimbledon, there are no more tour-level grasscourt tournaments left in North America. The former grass slots on either side of the Atlantic have been taken up by hard court events, many of which defend their position in the calendar having invested in their week of what’s now firmly a hard court swing.

But last week’s Hall of Fame Open in Newport illustrated how grass needs to be re-evaluated. In 2015, the owners of the Newport Casino (nothing to do with gambling, it’s an old-fashioned use of the word meaning ‘social club’, in this case with tennis courts) dug up their grass and re-laid the courts, profiting from the latest research. The result is a set of beautifully manicured lawns that play as true as any grass court. Even a week after Wimbledon, the tournament attracted an entry that included the former Wimbledon champion Andy Murray and others desperate for an extra week on grass.

So how much of the post-Wimbledon grasscourt season could be revived? The answer is probably two or three weeks. The four post-Wimbledon weeks include claycourt events for the diehard claycourters in European venues like Båstad, Gstaad, Hamburg, Kitzbühel and Umag, so why not a three-week grasscourt swing in Europe and America? There are still plenty of grasscourt venues in the US (it’s only 16 years since the American Davis Cup team played on grass at Rancho Mirage in California).

Some of the old British venues would still be viable. Frinton and Felixtowe are very august clubs which have kept their grass, while Ilkley has moved to a pre-Wimbledon slot as a Challenger tournament. The same cannot be said for Hoylake, where the empty tiers for the once fully occupied seats and the odd turnstile are like historical relics, and the lawns that once hosted the world’s greatest players are now available – sacrilege! – for kids to play football.

We cannot turn back the clock, tennis will not look like 1970 again. But the quality of grass courts is so good these days that some minor rebalancing of the clay/hard/grass distribution ought at least to be on the agenda. One tour player told me in Newport last week, “I’m not a great fan of grass, but at least you see different tennis than on hard and clay courts, and for that reason it’s great to play on.” In a crowded sporting market place, that’s as good a reason as any to consider an extra couple of weeks in the professional tennis year on the sport’s original surface.