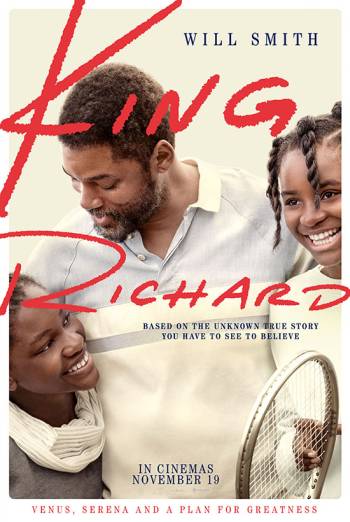

With the benefit of the hindsight provided by more than 22 years of the Williams sisters winning Grand Slam tennis titles, it’s easy to feel Venus and Serena were always going to achieve greatness. But there was nothing inevitable about the two women’s achievements, and the new film King Richard is a well-timed reminder of just what obstacles the family had to overcome.

Set against that benchmark, the film is a great success. But it’s also a success in other respects. It’s very watchable – at two hours 18 minutes a film can drag, but this one doesn’t. It has outstanding performances, notably from Will Smith, Aunjanue Ellis, Saniyya Sidney and Demi Singleton. And it has great attention to detail.

Films about tennis have a habit of assuming that viewers won’t notice when a Grand Slam champion really can’t hit the ball very well (the 2004 movie Wimbledon was perhaps the best/worst example of that). But in Battle of the Sexes (2017) Emma Stone made a visible effort to emulate Billie Jean King’s playing style, and credit should go to Eric Taino, the American-Filippino player who coached Sidney and Singleton for this film and really got them playing with all the wristy quirks of Venus and Serena (one Venus forehand volley is stunning in its authenticity).

A feature of any thought-provoking film is that you leave the cinema not sure if you like or hate the protagonists, and the beauty of Smith’s brilliant portrayal of Richard Williams is that you see both the glorious stubbornness of the maverick who won’t be told he’s wrong and the infuriating reality of dealing with him. I found myself whooping and wanting to strangle Williams within seconds of each other, and what is subtly but beautifully shown is the cracks in Richard’s and Oracene’s marriage that would eventually lead to divorce.

There are two elements that were left out of this film which are quite important.

The first is not crucial to the success of the piece as a movie, but it leaves one poignant scene unexplained. A big part of the drama centres on whether Richard will let Venus play a tour-level event in Oakland in October 1994. What is never explained is that on 1 January 1995 the women’s tour’s age eligibility criteria were going to change, which meant that any girl who hadn’t played a full-tour event by the end of 1994 had to play a truncated schedule until she was 18. That put a dividing line right through the foursome that was emerging as a superstar generation of the future: Martina Hingis and Venus Williams turned pro in 1994, while Anna Kournikova and Serena Williams missed the deadline.

For the film, that doesn’t really matter, though it takes an element away from the family dilemma of whether Richard should let Venus play in Oakland. But there’s a scene were Serena stands looking out on the empty Oakland stadium court feeling jealous of her sister, perhaps for the first time. The explanation that she would have to wait another three years for a similar chance despite being just 15 months younger is never offered.

The second omission is the murder of Tunde Price, Venus’ and Serena’s older sister, in 2003. The constant threat of violence and menace that accompanied the Williamses as they practised on public courts is well told, and obviously the success of the two sisters as adult players makes for a happy ending. But that menace claimed the life of their sister, and even a captioned mention at the end of the film would have been some acknowledgement that the social problems the Venus and Serena escaped from still exist.

Yet one of the great sensitivities of King Richard is that not all tension is painted as white v black, in fact very little is. While the country clubs into which the sisters are thrown are obviously all-white, some white kids are shown as seeing beyond skin colour, the Williams family always seem to see the people first and the race second, and an uplifting scene of autograph hunters near the end has as many white fans as black.

That all helps to make the point that the Williams sisters were not just a black phenomenon but a phenomenon full stop. A veteran tennis colleague of mine tells the story of how he walked into a New York shop during the US Open around 20 years ago, knowing full well that this was one of the city’s stores where talking about tennis was not going to get him very far, yet the shopkeeper volunteered the comment “Man, them Williams sisters, they sure are summ’n special!”

Their best playing days are behind them, and we may not see much more of Venus and Serena on court. But this film – made with significant input from the Williams family, which gives it factual credibility – serves to make the point that they are a social phenomenon. And that a father that breaks such a tough mould isn’t always going to be the easiest person in the world to get on with.