It was a solitary line at the very end of the film that triggered my curiosity.

The great and the good of British tennis were gathered in the Palace of Westminster, in the regal rooms of the Speaker’s chambers. The Speaker of the House of Commons, John Bercow, was not just the second-most powerful man in Britain at the time (the Speaker’s position in the British constitution immediately behind the monarch is underappreciated) but he’s a tennis nut. He’s an accredited coach, he knew Angela Buxton and knew that her son-in-law was, like him, an elected Member of the House of Commons.

Despite him being a controversial figure, I’ve always got on with John Bercow, though I can’t claim sole credit for that. When I say he’s a tennis nut, he’s even more of a Federer nut. And when he found out that I’m Roger Federer’s biographer, he became far more interested in me than he otherwise would have been. In fact I got used to him seeing me and saying with great gusto ‘Chris, hello, how – ’ and just when I expected him to say ‘How are you?’ he’d say ‘How’s Roger?’

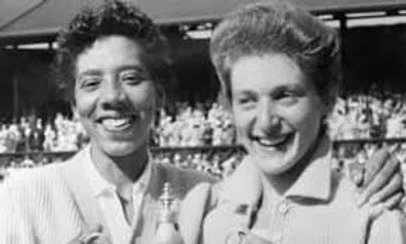

On this day, Bercow had agreed to host the British première of ‘Angela & Althea: a perfect match’, a film made about Althea Gibson and Angela Buxton winning the Wimbledon women’s doubles title in 1956. It’s a remarkable story of how two victims of social prejudice triumphed over that prejudice. Gibson a black American frequently denied practice and tournament opportunities because of her skin colour; Buxton a British Jew who came up against some of the worst of underhand British anti-Semitism.

In this era of Black Lives Matter and political parties trying to banish anti-Semitism, the film ought to have found a massive market, especially as it interviewed some high-powered people, among them two eminent tennis historians Bud Collins and Richard Evans, and the legendary Billie Jean King. Unfortunately, it was a family initiative with low production values, and no self-respecting TV station would have run with it because it was – regrettably – badly made.

I sat next to one of Wimbledon’s senior officials, and as the credits rolled, the very last line revealed that, despite reaching the singles final and winning the doubles, Buxton had never been made a member of the All England Lawn Tennis Club. I turned to my neighbour, inviting an explanation as to why not, but was met by equal puzzlement. ‘I don’t know, I’ll try and find out,’ was all I got.

A few weeks later, I ran into said official at a social event at Wimbledon and I asked whether the question about why Angela Buxton had never been made a Wimbledon member had been posed. ‘Yes,’ came the answer.

‘And?’ I asked.

‘There is a reason.’

‘And that is?’

‘I don’t think it’s appropriate for me to tell you.’

That was several years ago and I’ve kept it to myself. But with Angela having died a few days ago, I feel it’s now important that someone gets to the bottom of this. In an obituary earlier this week, The Guardian’s tennis correspondent Kevin Mitchell quoted Buxton from an interview she gave a year ago when she said of Wimbledon: ‘They haven’t given me membership, although they say they have. And I say: “What happened?” They said: “You refused it.” I said: “I don’t refuse it now. So send it along.” They said: “Oh, no, no, no, we can’t do that. You’ve gone to the end of the queue now.” This was 1980. It is a laugh – if you can see the funny side of it.’

There’s no point in denying that Angela Buxton could be a feisty sort, and it’s quite possible Wimbledon’s decision to withhold her membership was justified. But if it was a behavioural issue, then Wimbledon should say so, if only to remove any suspicion of anti-Semitism. No-one should be exempt from basic levels of civility because of their racial or ethnic heritage, though it’s important to recognise that accumulated prejudice can make it hard for victims of such prejudice to maintain civility.

In an era when more people in the world are trying to do the right thing by ethnic groups who have been the victims of prejudice over decades and centuries, Wimbledon should come clean about why they never gave membership to someone whose achievements would, by any other measure, have made membership automatic.

Photo: Gibson and Buxton on Centre Court with the trophy in 1956 (Bettmann/Bettmann Archive)