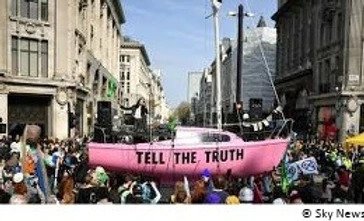

As provocative questions go, it’s hard to think of a more provocative or more insulting one than Adam Boulton’s on Sky News last week. ‘You’re a load of incompetent, middle-class, self-indulgent people who want to tell us how to live our lives?’ said the veteran political correspondent to a young climate protester who was trying to explain the rationale behind the Extinction Rebellion protests in London.

In a society governed by the rule of law, it’s inevitable that the police need to take action against protesters who bring the capital to a standstill, and I will go a long way to defend the right of journalists to grill all sides in a debate. But no-one should be under any illusion that these protests were coming, in fact we had ample warning of them more than 30 years ago. That’s why I feel my twentysomething alter ego is on the streets of London with the Extinction Rebellion folk (appalling name, but my generation weren’t exemplars of style either).

We all have our moments when we really ‘get’ something. I ‘got’ the environment in a lightbulb moment in my student days. It wasn’t about any of the buzzwords of the time – ‘the greenhouse effect’, ‘acid rain’, ‘hole in the ozone layer’, etc. It was a simple realisation that one of the strata of the earth that had taken millennia to form (I had the cross-sections emblazoned on my subconscious from school geography lessons) was being sucked out of the ground and simply burned, to no effect other than immediate gratification, and with no legacy other than a growing concern that we might be warming the planet.

That stratum was oil. The environmental debate is far more complex than just the impact of taking oil out of the ground to allow us to fly from London to New York in half a day, but it was the alarming simplicity of what we were doing that told me the environment was the crucial issue. Not the only issue – others like education and health were of great importance – but that without a healthy environment all else was secondary.

That was in the mid-1980s, and, as the months passed, the evidence grew that we were being profligate and irresponsible with our use of resources – yet very little happened. I regularly said to my then girlfriend ‘Why doesn’t the world see what’s blindingly obvious?’ In hindsight the answer was easy – there were too many big businesses who thrived off our fossil fuel economy.

In early 1987 I got a job in Switzerland, which opened my eyes to what a country can do when it takes the environment seriously. The culture there was to walk or take public transport unless it was hard not to, the local supermarket put my three cheeses in one bag to save packaging (something the generally responsible Waitrose doesn’t even do today), and we didn’t dare throw used batteries in the bin. When I returned to London in December 1988, I had a pitiful exchange in an electrical shop: I asked the shopkeeper ‘Do you do safe battery recycling?’ He looked at me mystified: ‘Chuck ’em in the bin like everyone else, mate!’ he replied. I got straight onto Friends of the Earth, asking whether I should report this pariah of the environment, only to be told that, while my indignation was entirely justified, regrettably it was common practice in Britain to throw batteries in the bin.

But there were signs of hope. In September 1988, Margaret Thatcher made a genuinely progressive speech about the environment, which gave the debate mainstream credibility. Eight months later, the Green Party polled 15% in the European elections (whether the Greens had policies that would have helped is questionable, but people frustrated about the environment often vote Green simply because they feel they’re sending a signal). It seemed there was no going back.

At the same time, the Channel Tunnel project was agreed. Initially it would be rail-only, but there was talk about there being a road link from about 2003 onwards. I knew that was a non-starter, because by 2003 it would be so clear that road transport’s future was dodgy that no-one would think of building a road tunnel under the Channel. I got that half-right, but only half.

Risk of eco-authoritarian regimes

And I wrote a very bad novel, which I later turned into a very bad play, depicting life in a UK society that had not tackled climate change and had therefore fallen into the hands of an authoritarian regime that had to severely limit energy use among the people. When working out the timeline that led to this society, I decided people would surely realise the threat of climate change by 2010, but played safe and decided that 2019 would be the year in which the world’s governments met to agree drastic energy quotas that simply could not be violated, which in turn led to the eco-authoritarian regimes.

We’re now in 2019, and governments have still not woken up to the climate threat. We have national treasures and respected scientists making it clear we’re heading for the scenario I described in my bad novel/play, yet governments still act with only the most cautious steps. Little wonder we have young demonstrators blocking central London with a pink boat, yet our response is to smile for a day, then move them on, and allow respected political interviewers to abuse them.

The twentysomething I was in the 1980s predicted this. I’m no clairvoyant – it was just blindingly obvious. Yet we chose to look away and carry on our life of blissful damaging ignorance. That’s why my alter ego is on the streets of London, and why the young demonstrators are indeed protesting in my name.